About Archaeopteryx

| Scientific Name (Genus) | Archaeopteryx |

| Meaning of Name |

Ancient wing

archaio (ancient) [Greek] - pteryx (wing) [Greek] |

| Classification | Saurischia, Theropoda, Archaeopterygidae |

| Total Length | Approx. 50cm |

| Diet | Carnivorous (insects, small animals, etc.) |

| Period | Late Jurassic (approx. 150 million years ago) |

| Species Name | Archaeopteryx lithographica |

| Year of Paper Publication | 1861 |

| Genus Name Publication | von Meyer, H. (1861). Archaeopterix lithographica (Vogel-Feder) und Pterodactylus von Solnhofen. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefakten-Kunde. |

The Shifting Throne of the 'First Bird'

Archaeopteryx, discovered in 1861 in the Solnhofen limestone of Germany, is a fossil creature possessing features of both dinosaurs and birds. Found shortly after the publication of Darwin's theory of evolution, it has held a special place in scientific history for over 150 years as a symbol of the 'missing link' and as the 'first bird.'

Archaeopteryx had asymmetrical flight feathers like modern birds, but it also retained distinct features of theropod dinosaurs, such as a jaw with sharp teeth, three-fingered claws, and a long bony tail.

However, since the 1990s, the discovery of numerous fossils of bird-like feathered dinosaurs in China, such as Anchiornis, has led to a major reassessment of Archaeopteryx's position. It is now widely believed that while Archaeopteryx is located near the base of the evolutionary tree leading to birds, it is one of many 'bird relatives' and not a direct ancestor of modern birds.

Black Wings and Limited Flight

The extent to which Archaeopteryx could fly has been a long-standing debate. The structure of its shoulder joint would have prevented it from raising its wings fully upward, making powerful flapping flight like that of modern birds impossible. Its sternum, where flight muscles attach, was also small and undeveloped. However, its asymmetrical flight feathers were suitable for generating lift, suggesting it had the ability to glide from tree to tree or make short jumps with a running start.

In 2011, analysis of preserved melanosomes revealed that some of its feathers were black. This black pigment (melanin) would have strengthened the feathers, potentially aiding its flight capabilities. It is suggested that the feathers on its forelimbs and tail were likely a base of black or dark gray, possibly with white stripes. If these feathers were used for display in courtship rituals, Archaeopteryx might have attracted mates with a beautiful, high-contrast appearance.

The Solnhofen area, where the fossils were found, was a series of islands in a shallow tropical sea at the time. It is believed that Archaeopteryx lived on these islands, preying on insects and small animals.

Archaeopteryx as a Bird

Archaeopteryx has a wing structure similar to that of modern birds.

Archaeopteryx is not considered a direct ancestor of modern birds.

Its flight feathers are asymmetrical, with fine barbs (less than 1mm thick) branching off the shaft. Each barb, in turn, has smaller branching barbules, many of which have tiny hooks called barbicels. These hooks interlock with adjacent barbs to form a solid, cohesive vane.

Archaeopteryx possessed this structure, which is well-suited for flight. However, whether it could achieve powered flight or was limited to gliding from trees remains a topic of debate.

As mentioned earlier, recent studies indicate that Archaeopteryx is not a direct ancestor of modern birds. While it was an early bird, it does not fall on the evolutionary branch that leads to modern avians. The extent of avian diversity during the Late Jurassic (about 146 to 141 million years ago), when Archaeopteryx lived, is not fully understood.

Archaeopteryx as a Theropod Dinosaur

When Archaeopteryx was discovered in 1861, it was common knowledge that having feathers meant being a bird. Therefore, it was classified as such.

However, since the 1990s, numerous feathered dinosaurs have been discovered in places like China.

Many traits once considered exclusive to birds were found to be common among a broader range of theropod dinosaurs (especially in groups called Maniraptora and Paraves). Shared traits like hollow bones, a wishbone (furcula), complex feathers, and long, wing-like forelimbs have blurred the line between dinosaurs and birds, making it difficult to determine where one group ends and the other begins.

While Archaeopteryx is classified within Aves [Class] - Archaeornithes [Subclass] - Archaeopterygiformes [Order] - Archaeopterygidae [Family], it is also considered a type of dinosaur, belonging to Saurischia [Order] - Theropoda [Suborder] - Tetanurae - Coelurosauria - Maniraptora.

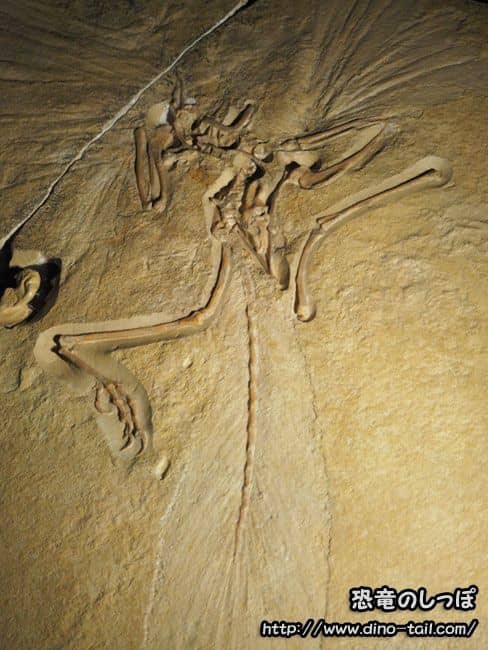

Excellent Preservation - The Solnhofen Environment

150 million years ago, the Solnhofen region was surrounded by coral reefs, forming a lagoon with poor water circulation with the open sea. In the bottom layers, the water tended to stagnate. The warm, dry climate promoted evaporation, causing highly saline water to accumulate at the bottom, resulting in an anoxic or hypoxic environment. This was a harsh environment for living organisms.

Such conditions also made it difficult for decomposing bacteria and bottom-dwelling scavengers to thrive. Therefore, when creatures like Archaeopteryx fell into the lagoon or were washed in by storms, their carcasses were buried in fine mud without being decomposed or eaten, preserving them almost perfectly.

This process not only preserved articulated skeletons but also left clear impressions of extremely delicate tissues like feathers.

Solnhofen Museum - Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum, Germany.

Archaeopteryx is not the only fossil found in Solnhofen. These discoveries tell us how diverse the ecosystem was at the time. The area around the lagoon was inhabited by a wide variety of creatures, including ammonites, squids, pterosaurs, crustaceans, and insects.

This collection of well-preserved fossils provides a valuable source of information for studying the detailed food web of the Late Jurassic, from marine invertebrates to flying vertebrates.

Major Archaeopteryx Specimens

The specimen on which Hermann von Meyer based his 1861 description of Archaeopteryx was a single feather, known as the "Single Feather."

There are numerous Archaeopteryx specimens, often named after the location where they are housed.

The London Specimen (Specimen number BMNH 37001)

Discovered in 1861, this was the first skeletal fossil found. Although it lacks a skull, it preserves beautiful feather impressions, with most of the body saved on a limestone slab measuring 60cm by 40cm. It made its mark in scientific history as important evidence supporting Darwin's theory of evolution.

The specimen, unearthed near Langenaltheim, Germany, in 1861, was given to a local doctor in exchange for medical services and was later sold to the Natural History Museum in London for 700 pounds. In 1863, Richard Owen at the British Museum of Natural History identified it as 'Archeopteryx macrura.' This name was invalidated in 1961, and it is now considered 'Archaeopteryx lithographica.'

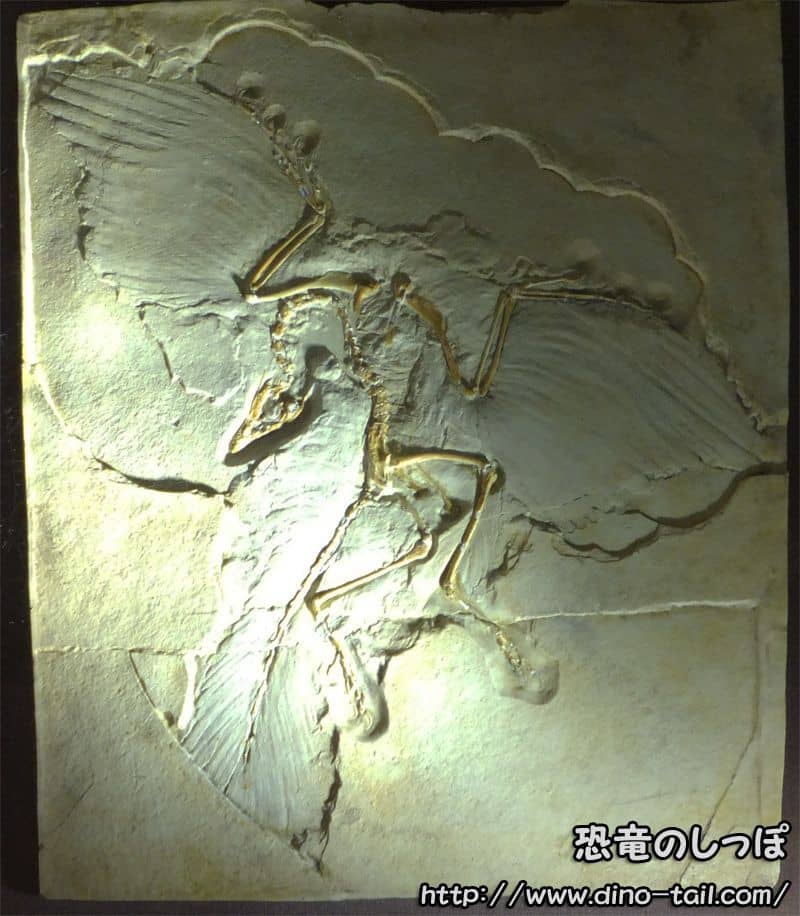

The Berlin Specimen (Specimen number HMN 1880/81)

Discovered in 1874 or 1875, this is the most complete and beautiful specimen. On a limestone slab measuring 46cm by 38cm, it includes the skull and nearly the entire skeleton, often hailed as "the world's most beautiful fossil." The image we have of Archaeopteryx is largely based on this specimen.

The specimen was found by a local farmer near Eichstätt, Germany, in 1874-75. In 1876, the farmer sold the fossil to buy a cow. Between 1877 and 1881, it passed through the hands of several buyers before finally being acquired by the Natural History Museum in Berlin (for a reported 20,000 Goldmarks, a gold-standard currency equivalent to 7168.4g of pure gold. A bargain, considering its value?).

Being a complete specimen including the head, it was described as a new species, 'Archaeopteryx siemensii,' by Wilhelm Dames in 1897.

The original specimen is housed at the Natural History Museum in Berlin (Humboldt Museum). Replicas are displayed in many other museums and are also produced for sale to fossil collectors.

The Solnhofen Specimen (Specimen number BMMS 500)

Discovered in 1987, this specimen is notable for its large size compared to others. Although it is missing parts of the head and neck, the rest is well-preserved. It was initially described as a separate genus (Wellnhoferia), but the current consensus is to consider it a species of Archaeopteryx.

This specimen is owned by the municipality of Solnhofen, where it was found.

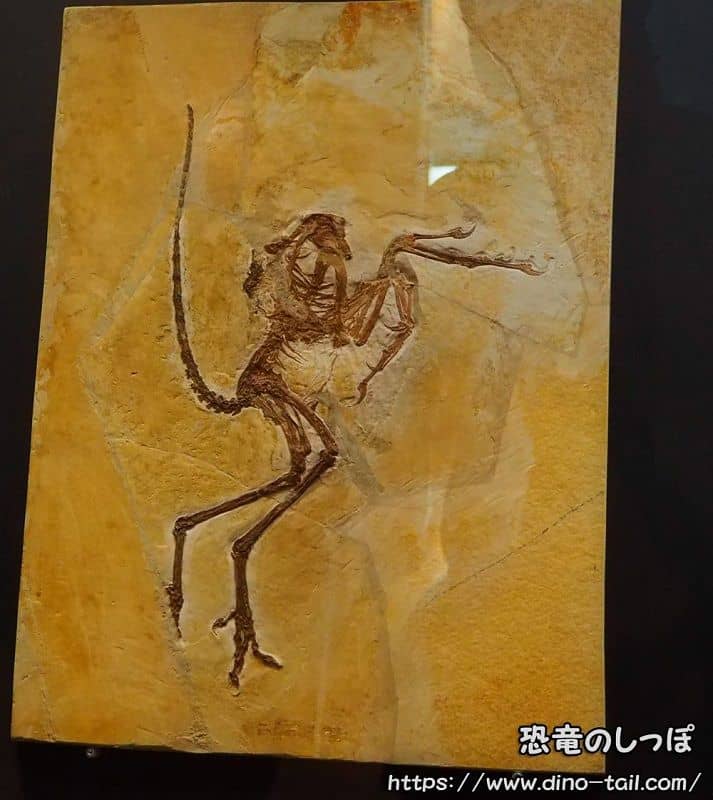

The Haarlem Specimen (Teylers Specimen) (Specimen number TM 6428/29)

Discovered in 1855 near Riedenburg, Germany, this is a partial fossil on a limestone slab measuring 23cm by 12cm, preserving parts of the hindlimbs and forelimbs. It was described as the pterosaur 'Pterodactylus crassipes' by Hermann von Meyer in 1857, but was reclassified as Archaeopteryx by John Ostrom in 1970.

In 2017, it was further reclassified into the genus 'Ostromia.' It is thought to be closely related to the Chinese theropod Anchiornis.

It is currently housed at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, Netherlands.

The Eichstätt Specimen (Specimen number JM 2257)

It has been suggested this may be a different genus.

Discovered in 1951 near Workerszell, Germany.

This specimen is a plate and counterplate pair, presumed to be a juvenile.

It was described by Peter Wellnhofer in 1974 but may belong to a different genus, Jurapteryx.

It is housed at the Jura-Museum in Eichstätt, Germany.

The Munich Specimen (Specimen number BSP 1999 I 50)

Discovered in 1992 near Langenaltheim, Germany, this specimen was previously known as the Bavarian Specimen.

The slab measures 53cm by 43cm. Although missing the upper jaw, the rest is in complete condition.

It was described in a paper in 1993 by Peter Wellnhofer, then curator of the Bavarian State Collection for Paleontology and Geology. He also described the Eichstätt specimen and is known for his research on Archaeopteryx specimens, as well as being a renowned authority on pterosaurs.

A 2009 study suggested the individual was about 300 days old. What was initially thought to be a sternum was later identified as part of the pubis. Recent research suggests it may belong to the species 'Archaeopteryx siemensii,' like the Berlin Specimen.

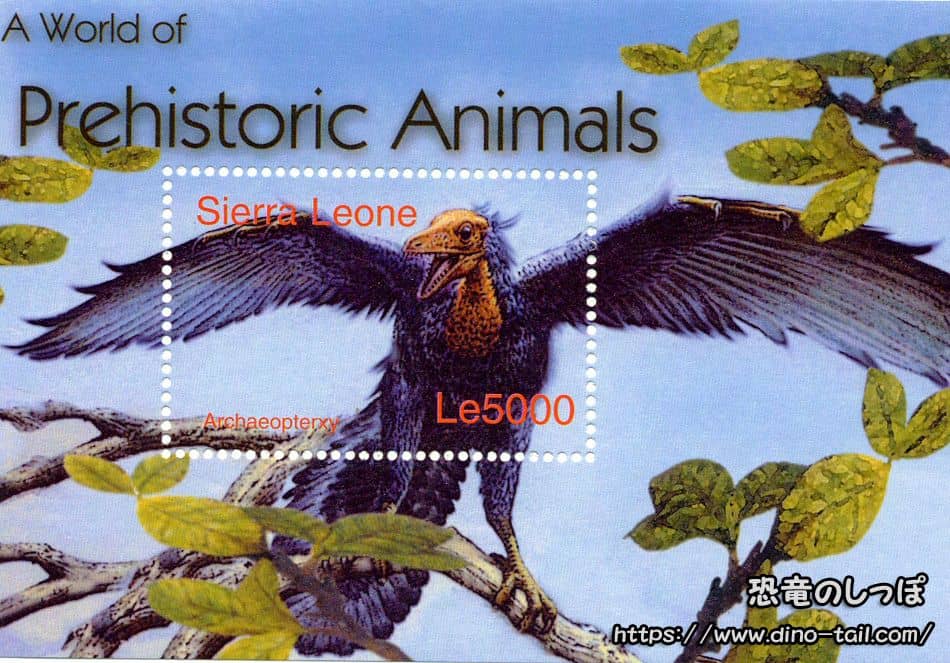

Archaeopteryx Stamp & Fossil Gallery